This blog article was written by a guest writer, Jessica Wenclawiak.

On March 15, 2000, scientists Ken Balcomb and Diane Claridge walked along the beach in the North Bahamas and quickly became involved in a disturbing event: 17 marine animals, including 14 beaked whales, were stranded on the shore. Rescuers attempted to save every animal, but only ten returned to the ocean that day. This sudden stranding became more perplexing when researchers learned that the U.S. Navy had conducted routine sonar exercises 36 hours prior, leading researchers to question whether this noise had caused significant, and even fatal, problems for the animals. Although research has been inconclusive, many scientists recognize that the sonar exercises could have played a role in the strandings. Although this event may seem singular, scientists have studied the influence of anthropogenic noise on marine life for decades, leading us to wonder how human activity in the ocean has changed the marine living environment.

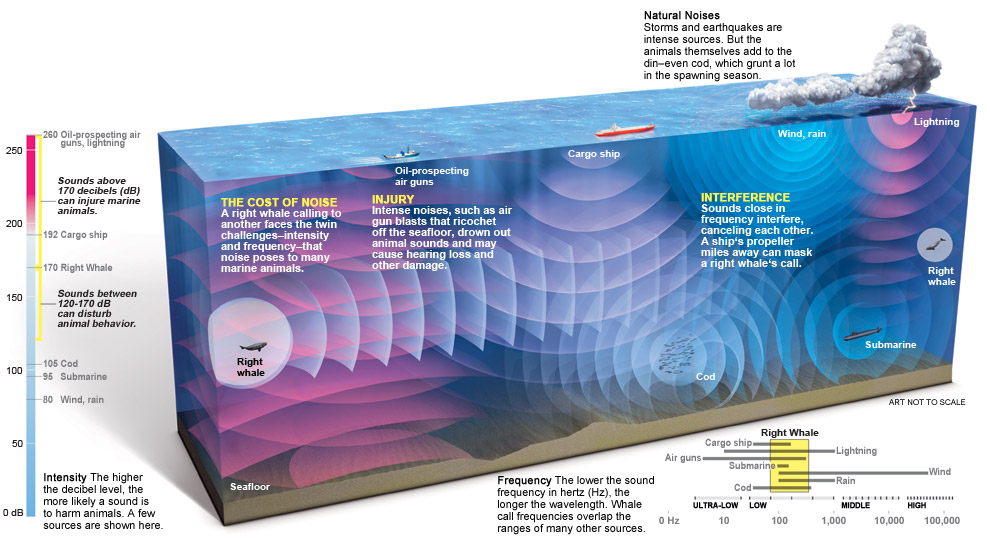

For most of us, the ocean is a symbol of serenity, with its soothing waves and gentle breezes. Under the surface, however, you would find a deafening cacophony of sounds, both natural and man-made. Earthquakes, lightning, echolocation clicks, whale song and many other sounds made by marine species, and even the movement of water particles are all noises outside the range of human hearing that impact marine life. As such, it is difficult to imagine how our activity can affect and add to this constant din, but it does. Ship traffic, seismic explorations, and sonar all bring new noises into an ocean already full of sounds.

These sounds may seem insignificant to us, but for mammals such as whales and dolphins, they can be both deafening and dangerous. Seismic air guns that are shot underwater in the process of petroleum and mineral extraction, for example, give off noises between 200-240 decibels (dB). In the air, this level of sound is around 140-180 dB—the same level as that of jet engines at take-off. When these overwhelming noises dominate the environment, there is a chance for temporary hearing loss and increased stress. In areas with high ship traffic, some marine mammal species have been observed abandoning their usual habitats or moving to shallower waters to avoid the noises, increasing their risk of stranding. Although research is still inconclusive on which characteristics of noise are most damaging to an organism—be it volume, frequency, or location—experiments and observations show that two of the most common effects of anthropogenic noise on marine mammals are difficulty locating and communicating with other members of their social group and interfering with the use of echolocation to find prey and avoid threats, leading to increased risk of ship strikes and interference with feeding and mating activities.

With these effects in mind, scientists are continuously conducting more research to pinpoint which frequencies and noise levels are most detrimental to marine organisms. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Association (NOAA) has produced strategies for monitoring noise pollution, but the recent increase in global trade and seismic exploration could make the creation of guidelines or regulations that protect marine life difficult to implement in the near future. These uncertainties lead us to question what the future will look like—or sound like—for marine life and whether or not the current efforts to create regulations will be effective.

For sources used in this blog and additional resources on this topic, please see the Resources page.

Photo credit for the featured image goes to the National Aquarium.