“When we try to pick out anything by itself, we find it hitched to everything else in the universe.” ~John Muir

Many of our GDEP blog pieces to date have featured species-specific information or issues explicitly impacting marine organisms and systems. Today, we are taking a broader approach and exploring something that impacts terrestrial and marine systems alike: extinction. Ecology is a science of connections and relationships; what happens in one system will ultimately impact what happens in another. What do a Mammoth and a Marine Mammal have in common? Find out below.

The celebratory tone of the gathering was momentarily dampened as Dr. Beth Shapiro arrived at the slide reading “Extinction is Forever.” The words were sharp and definite, a white scroll framed in ominous black. Shapiro—author of “How to Clone a Mammoth: The Science of De-Extinction,” biologist and professor at UC Santa Cruz, and alumna of UGA’s Odum School of Ecology—delivered the keynote address at the recent celebration of the 50th anniversary of the school. Shapiro discussed her research in de-extinction—in simple terms, the science of making an extinct species un-extinct. But with this slide, Shapiro reminded the audience that there is nothing simple about de-extinction.

Photo credit: Harvard Book Store on Twitter

Many scientists agree that we are now in a sixth extinction, and though some extinctions are a result of natural evolutionary processes, many are not. Elizabeth Kolbert’s book of this namesake—“The Sixth Extinction: An Unnatural History”—explores human contributions to a time period that will likely be marked by enormous reductions in biodiversity, on the order of 20 to 50 percent of species within the century.

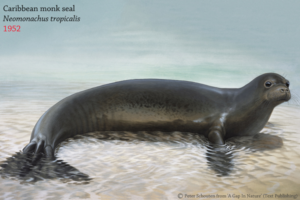

Marine or terrestrial, no system will be spared the casualties of the sixth extinction. In her book, Shapiro notes that “The Yangtze River dolphin is an example of how pollution, combined with habitat destruction, can lead to extinction.” The vaquita may soon follow in its footsteps. A 2015 Science review reported 15 global marine animal extinctions compared with 514 terrestrial animal extinctions over the last 514 years. Researchers fear that slow-progressing marine extinctions may soon gain momentum due to increasing industrialization of the oceans.

This information is not new to many of us. We hear about it with ever-increasing frequency. The pile of evidence documenting detrimental human impacts on the environment grows. The conversation about these assaults is rich with the voices of conservationists, scientists, and others urging action. Scientists warn that, among other action items, if we do not lower carbon dioxide emissions by 2020, our negative effects on the environment may be irreversible. Projects like the Photo Ark, founded by Joel Sartore, aim to address our negative impacts in innovative ways, capturing images of species and landscapes before they disappear and trying to engage the public in caring about the plight of the life with which we share the world before it’s too late.

Photo Credit: National Geographic Store

At a time where humans are being incriminated in a host of ecological ills, de-extinction sounds like a welcome relief, an option to undo some of the harm, a second chance. But the science behind de-extinction is complicated, and Shapiro notes that in order to bring an extinct species back, one must have access to a living cell. This greatly limits the options of what can be brought back to life.

Photo credit: Karen Kasmauski/Getty Images

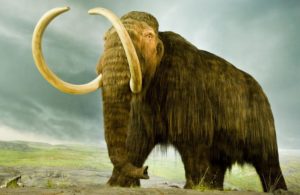

In short, Shapiro writes that there are two options considered when thinking about de-extinction. One involves having access to an intact cell taken from a living organism and cloning the species—think nuclear transfer and Dolly the sheep. The second involves sequencing an extinct animal’s genome and cutting and pasting relevant portions into a close living relative’s genome. Shapiro uses the example of the mammoth and its closest living relative, the Asian elephant. Will this approach bring back a mammoth? No. Will it create an Asian elephant with mammoth-like features that better equip it to live in colder environments? Maybe. In the words of science writer, Brian Switek, “… Any revived species would be the beginning of something new, rather than the restoration of the old.”

Photo credit: National Geographic Kids

But the science is not the only complicated aspect of de-extinction. Shapiro reminds us that before we take steps to revive a species, we must determine which species are eligible for de-extinction and answer a series of critical questions. Why did they go extinct in the first place? Will this process repeat itself if causal factors are not addressed? Will re-introducing a species cause harm to a system that has adapted to its absence? How will bringing this species back influence other species within a given system?

In her book, Shapiro writes that the true value of de-extinction lies less in recreation than in restoration. In her words, “Extinct species are gone forever. We will never bring something back that is 100 percent identical—physiologically, genetically, and behaviorally identical—to a species that is no longer alive. We can, however, resurrect some of their extinct traits.”

John Muir’s eloquent words become a bit more unsettling when spoken in this context. ““When we try to pick out anything by itself, we find it hitched to everything else in the universe.” When extinction occurs, something disappears and the universe changes. Although de-extinction holds promise for restoring threatened systems and species, once we have changed that universe, we will never be able to fully recreate what we have lost.

For sources used in this blog and additional resources on this topic, please see the Resources page.