The FDA and EPA have posted advisories for expectant mothers and infants, cautioning them to avoid eating certain fish in high—or in extreme cases, any—quantities. Why the cause for such concern? Mounting scientific evidence has found that the high levels of mercury in fish transfer through the food chain, posing the threat of mercury poisoning to humans with fishy diets. However, one group is at even greater risk from mercury than humans: marine mammals.

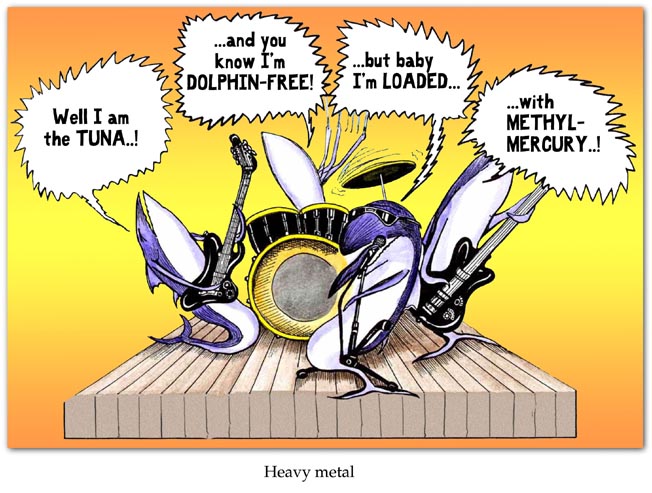

Mercury travels up the food chain and stays in the tissue of animals for their entire lives; the older the animal and the higher its position in the food chain, the higher mercury loads it will carry. Marine animals, like the tuna pregnant women are encouraged to avoid, are at particular risk because much of the mercury released into the atmosphere settles in the oceans. Marine mammals’ fish-based diet and their top spot in the food chain put them at extremely high risk for mercury poisoning.

Mercury is emitted into the air from many sources, but the major contributors are the burning of coal, oil, wood, natural gas, medical and municipal wastes and the process of gold mining. Once mercury lands in the ocean, microorganisms convert it into its organic and most toxic form—methylmercury.

Methylmercury stores preferentially in the liver, and it reaches levels in seemingly-healthy marine mammals that could kill a human several times over. Marine mammal cells are more naturally resistant to the effects of mercury than human cells, but another heavy metal, selenium, also plays an important role. Selenium exists in high levels in fish and other marine life, and it acts as a counteragent to mercury. When selenium binds to methylmercury, it renders it inert and harmless.

So, it’s all good, right? Selenium takes care of the mercury and healthy dolphins abound? Sadly, no. The mercury intake outpaces selenium’s ability to bind to it. Mercury causes neurological and immunological impairment, leaving marine mammals lethargic, anorexic, and riddled with diseases their immune systems are too weak to fight off.

Today, less than 50% of wild dolphins examined can be classified as healthy.

Two studies conducted in Indian River Lagoon in Florida and Charleston, South Carolina found that bottlenose dolphins in the Indian River Lagoon population have among the highest mercury loads in the world, a staggering five times higher than in the neighboring Charleston population. Mercury contamination is of great concern for marine mammals across the world, but scientists have also come to understand marine mammals’ mercury loads as an indicator of human health. After all, we eat the same fish they do.

A study of 135 coastal residents in Florida found over half of the participants had mercury concentrations exceeding the exposure guidelines established by the EPA. The main channel through which mercury reaches humans is through seafood consumption, so coastal residents are at particular risk. Fortunately, we have many sources of information to use in protecting ourselves from mercury exposure, including wallet cards with reminders of which fish contain the lowest mercury levels.

Marine mammals, however, have no option to cut back on their tuna intake, nor is there currently any way to treat or prevent mercury poisoning in marine mammals. Scientists believe the cause of these heavy loads is the increased burning of mercury-containing materials releasing more mercury into the air. While the sources and effects of mercury are well understood, a solution for marine mammals remains elusive.

This piece is part of the Ecotoxicology series.

For sources used in this blog and additional resources on this topic, please see the Resources page.

Featured image: infographic from fix.com, created by NRDC, Huffington Post, Heart.org, and Seafood.edf.org