GDEP team member, Talia Levine, recently had an article published in Georgia Health News. Her article, featured below, explores shared wildlife and human health risks surrounding a Superfund site on the Georgia coast.

When pollutants escape into our waters, the food chain suffers

Published Nov. 1, 2017 by Georgia Health News

Daniel Parshley slices through a sea trout’s flesh with a quick, clean motion. His instructions are a chant, well-rehearsed, now seemingly part of his muscle memory. Remove the skin, cut off the fatty parts, lose the belly flap, repeat.

Seagulls fly overhead, watching the action, and one dive-bombs a former comrade perched contentedly on a pile. Friendships dissolve when fish filets are up for grabs.

There’s a reason why Parshley knows his way around a fish.

Parshley began working with the Glynn Environmental Coalition (GEC) just after its inception in 1989, and he became its project manager shortly thereafter. Glynn County, along the Georgia coast, has housed a multitude of industrial operations, and it is now home to four active Superfund sites. These sites are highly contaminated, with hazardous materials present that negatively affect both human health and the environment. They are designated as priorities for cleanup by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA).

The GEC advocates for a clean environment and a healthy economy for residents while engaging affected communities in the decision-making process for the Superfund sites.

One such site, Linden Chemicals and Plastics (LCP), has gained much attention over the past decade as researchers have studied the impact of mercury and polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) that originated at this site and contaminated the neighboring Turtle Brunswick River Estuary. PCBs are industrial chemicals, banned since the late 1970s but still doing damage where they exist.

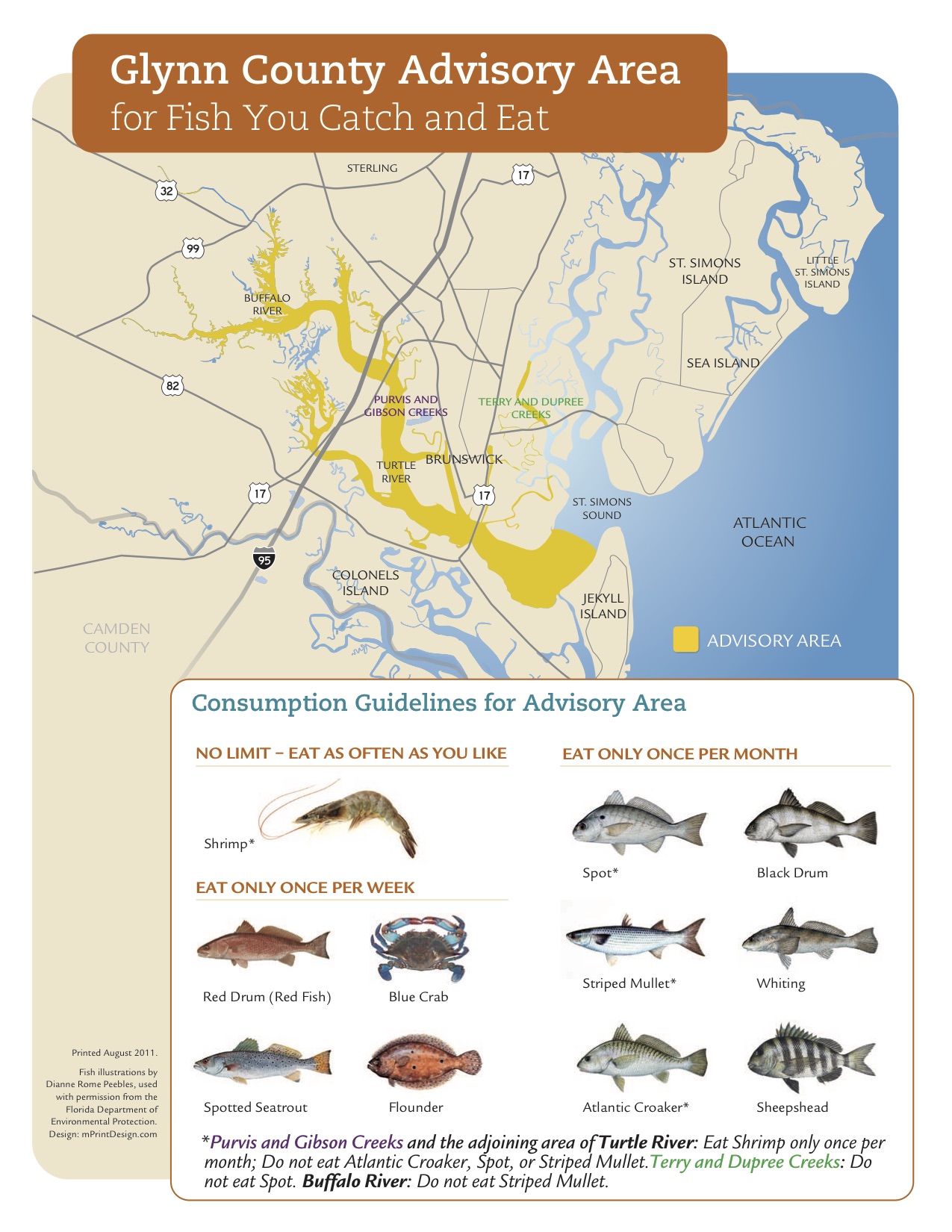

Part of the GEC’s role in providing outreach and support for local communities is spreading the word about fishing advisories. Administered by the Georgia Environmental Protection Division, these advisories instruct residents on how to modify consumption of species from compromised waters.

“They recommend that only the filet be eaten,” Parshley notes. “The reason for that is to remove the fatty portions of the fish. Some of the harmful chemicals, like PCBs, accumulate in the fats, also known as lipids, but things like mercury are more generally distributed through the fish.”

Advisories differ by fish species, but Parshley says, “As a general rule, the fattier the fish, the more contaminated, and the less you should eat it. Spots and croakers have been identified as being particularly contaminated, as have mullet.”

Women and children are especially vulnerable to the effects of contaminants such as PCBs and mercury.

The Safe Seafood Program — a partnership between the GEC, the University of Georgia, Sea Grant, the Georgia Department of Public Health, the Glynn County Health Department, and the Georgia Department of Natural Resources — educates people about the risks of contamination in seafood from affected areas.

Parshley says women of childbearing age and children younger than 7 should be especially cautious in preparing and consuming seafood from the advisory areas, and he recommends that they eat fish from outside the advisory area whenever possible.

“The children are developing young brains and bodies and neurological systems, and women, because these chemicals accumulate in fatty tissue, will accumulate them over a long period of time and then release them during pregnancy when the body needs that extra energy during the child’s fetal development.”

Dolphins suffer the consequences

Although there are fishing advisories in place to protect the most vulnerable humans, no such protection is afforded to the wildlife that call this area home.

Brian Balmer and his colleagues published the results of a 2009 dolphin health assessment they conducted in the journal Science of the Total Environment in 2011. Claiming a record that no one would want, male dolphins in Brunswick were identified as having the highest levels of PCBs of any marine mammals in the world.

“A local bottlenose dolphin in an estuary of Georgia has levels that are actually higher than a transient killer whale, which is several trophic levels higher than a bottlenose dolphin, where it’s a marine mammal eating other marine mammals. You look at a bottlenose dolphin in Georgia, and those levels are actually much higher than that,” says Balmer, a scientist with the National Marine Mammal Foundation. “I just don’t know how these animals are actually still reproducing and surviving with these screaming high levels of contaminants.”

Sapelo Sound, an ocean inlet between two Georgia barrier islands, was set as a reference site for this study. Dolphins in the area surprised researchers with PCB levels comparable to the former Southeastern U.S. record-holders — the dolphins of Biscayne Bay, Fla.

Although there are still questions about how contaminants are transmitted to wildlife and humans alike, researchers believe prey species (i.e., the creatures they eat) are the primary route of exposure.

John Schacke, principal investigator and science director of the Georgia Dolphin Ecology Program, is familiar with the effects of this exposure.

Schacke’s organization researches the basic dynamics and ecology of dolphin populations along the Georgia coast. Although the dolphins that he studies seem to be in relatively good health, he assumes populations in the central area of the coast are likely carrying high loads of PCBs, based on their proximity to Sapelo Sound (the southern extent of his study area) and on the high PCB levels noted in this population by Balmer’s team a few years ago.

Contaminant exposure in dolphins can lead to a host of ill effects.

Schacke mentions respiratory problems, skin lesions, lesions in the brain that can impact cognitive abilities, and disruption of endocrine functioning and reproductive success as potential health effects of PCBs and other contaminants in these mammals. In his view, reproductive effects can be particularly damaging as subsequent generations will be negatively impacted, possibly threatening the overall viability of the entire population.

Balmer noted other ill effects in the 29 dolphins sampled during his 2009 health assessment. “Twenty-six percent of the animals that we handled had this high prevalence of anemia, and in looking at primate studies, that’s one of the things you see with a high PCB exposure.”

Dolphins are just one of the types of animals that feed in this marsh system, and researchers are currently investigating how other wildlife may be impacted.

Richard Bauer, a master’s student at the University of Georgia who conducts his research with Dr. Kimberly Andrews’s Applied Wildlife and Conservation Lab in Brunswick, is interested in the prey species that humans and wildlife share. His study will examine PCB, mercury and lead contamination in American alligators, loggerhead sea turtles and diamondback terrapins, three species of vertebrates that share similar life spans with humans.

“In addition to being long-lived, they’re also eating the same things that people are eating,” Bauer says. While they are spending portions of their life stages in the marsh, loggerheads feast on blue crabs and alligators enjoy meals of crab, shrimp and game fish, such as mullet and red drum.

Advice is good only if heeded

It goes without saying that animals do not clean their fish prior to consumption, as people have the ability to do. But health effects in dolphins and other species of wildlife may be more relevant to humans than we would suspect, because some human populations consume whole fish from compromised waters, rather than sticking with filets as the advisories recommend.

Parshley has noted a number of challenges to compliance with the guidelines in coastal Georgia.

“The advisory itself is not well known,’’ he said. “It has to be a constant public education campaign to keep that before the public.” Besides, he says, how people prepare fish for their tables is often a matter of habit and “cultural preferences.” Though experts may warn that only the filet and not the whole fish should be eaten, “the way people have historically prepared the seafood still goes on.”

Parshley is also concerned that people often underestimate their portion sizes and servings. They may be consuming more food than is good for them, and that’s especially a problem if the food is fish from an advisory area.

Above, Seafood advisory map for Glynn County. Credit: Glynn Environmental Coalition

The shared reliance of humans and wildlife upon food resources is of concern to scientists familiar with Glynn County’s legacy of industrial contamination. Dolphins are not only apex predators at the top of the marine food chain, but also a sentinel species. “It manifests the conditions of the environment in which it lives,” Schacke offers as a definition of a sentinel species.

“They’re sort of like the canary in the coal mine,” Parshley says. “They give forewarning of risk to people. For instance, the dolphins have immune problems and skin lesions, thyroid problems. Birds are having reproductive problems and immune problems also. These are the sentinels out there telling us that we need to get this area cleaned up and that there are risks to people eating the same seafood. After all, we’re animals too.”

Parshley throws the discards from the fish cleaning lesson into the murky waters. We’re not too far from the Turtle River. The gulls dip and dive, set against the golden background of the late-afternoon sky over the marsh. In the swirl of feathers and squawking, it is easy to remember that we are indeed all animals relying upon the same resources.

For sources used in this blog and additional resources on this topic, please see the Resources page.

Featured Image: Dolphins in Barbour Island River. Photo credit: Georgia Dolphin Ecology Program