“We need more water!” my nephew demands. I trudge into the ocean, neon-green plastic bucket in hand, to do as I’m told. My bucket disappears from view as I dip it beneath the waves, but it re-emerges, heavy with the smell of salt water. As I make my way back to the tiny blonde dictator sitting in the sand, I pass three cigarette butts, an empty Ziploc bag, and a sand-filled straw. My nephew is dredging a moat in front of his sandcastle, and he pays no mind to the abandoned plastic shovel beside him, as he already has his tools in hand. My bucket is a found treasure, gifted to us (be it unknowingly) by another family. They left it bobbing in the tide pool as they hurriedly rushed their crying toddler off the beach. I snag the plastic shovel from their abandoned post and begin digging as the sky burns late-afternoon orange and pink. I have a moat to make.

The beauty of the Georgia coast is payment made for enduring the swampy heat and mosquitos of the endless summer. I am saddened when I see what’s left on the barrier-island beaches of my childhood at the end of the day. I challenge anyone reading this to offer evidence of a pristine beach untouched by human hands or an ocean without a plastic bottle bobbing like a buoy on its surface. No such place seems to exist anymore.

In May of this year, Ed Yong of The Atlantic reported on Henderson Island—an island in the South Pacific he described as “the most remote place you can visit without leaving the planet.” Yong said that one need only take a virtual tour via Google Street View to reveal litter tarnishing the white sands. Plastic, plastic, everywhere. Researchers who visited the island saw purple hermit crabs re-homing in plastic pieces instead of shells. Yong reported: “Every square meter of Henderson’s beaches has between 20 and 670 pieces of plastic on the surface and between 50 and 4,500 pieces buried in the topmost 10 centimeters.”

Sadly, this may not be the most bizarre debris-related discovery of recent times.

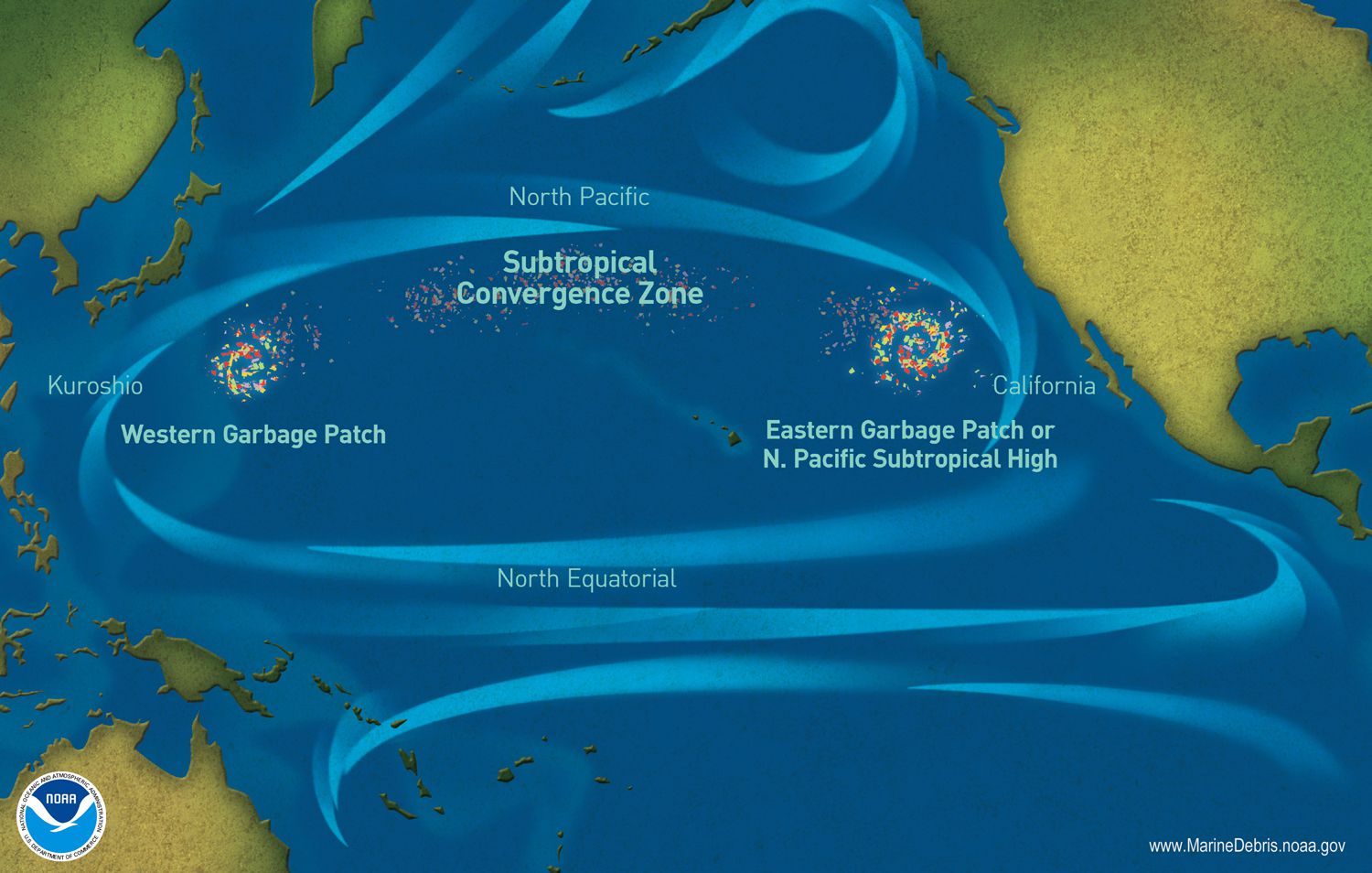

The Great Pacific Garbage Patch, also known as the Pacific trash vortex, is found in the North Pacific Ocean. Made up of two distinct spinning garbage patches, it is encircled by the North Pacific Subtropical Gyre—its circular motion pulls debris to the center where it remains. According to The National Geographic Society, approximately 80% of its inputs come from North America and Asia and from land-based, rather than marine-based, activities.

Although a swirling garbage patch is hard to ignore, most marine debris is far subtler. It is ubiquitous in the environment, and it causes more harm than our casual notice of it might suggest.

In a 2007 study in the Journal of Polymers and the Environment, Seba Sheavly and Kathleen Register said that a review of available data on the subject showed that most debris comes from things we consume (food and beverage refuse, as well as cigarettes and related products), items used to transport us by sea, and items used for marine harvest (i.e., fishing gear).

Sheavly and Register noted the myriad impacts marine debris has on aesthetic and economic interests, the health of wildlife, and human affairs. Tourist communities suffer economic consequences from litter-strewn beaches. Wildlife are killed or injured when entangled in abandoned fishing gear or when they mistake marine debris for food. And according to researchers, ghost fishing—in which abandoned fishing nets continue to trap marine organisms—negatively impacts both wildlife and fisheries.

The list of ills is disheartening. Buried in this study, however, is a quote that is more disturbing with each reading:

“Every piece of debris and litter found in our waterways at one point involved a person who made an improper decision. In a way, it can be said that every piece of debris has human fingerprints on it.”

Our fingerprints incriminate us: the debris swirling in the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, the litter on remote Henderson island, and the monofilament line entangling a dolphin all bear our prints.

But fingers were made for more than pointing and placing blame. Just as our prints have gotten us into trouble, they may also be able to improve our situation. Sheavly and Register have this to say: “Marine debris (marine litter) is one of the most pervasive and solvable pollution problems plaguing the world’s oceans and waterways.”

In the next few months, we will share how humans of all walks are already working towards solutions. We will also explore how others just learning of the magnitude of this issue can begin to make changes. For any solution to be truly effective, we all must take part.

It’s time to leave the beach, and my nephew’s reluctance gives way to excitement when he hears there’s ice cream at home. He collects his neon-green bucket and I put the abandoned shovel in our wagon. I take his hand and tell him he will need his other hand free; we’re going to play a game. You point out the trash on the beach, and I’ll pick it up! Everything’s fun when you’re 3 years old. We run as fast as we can, and I shove half-buried cigarette butts, food wrappers, and abandoned beach toys in the plastic bag I saw rolling down the beach like a tumbleweed. He asks why we’re collecting trash and I tell him animals eat it and it makes them sick. He sees a bucket left by another child—this one is bright blue. We race to it together, and now he is tired. I prop him on my hip and carry him off the beach, his plastic treasure clasped in his hand, his fingerprints on the handle.

This post is part of a recurring series, “Good for you, Good for the ocean.” In the coming months, we will examine a number of issues impacting marine and human health. As part of this series, we will explore marine debris in greater depth, looking at how it is transported, the impact of microplastics, what you can do, and more!

For sources used in this blog and additional resources on this topic, please see the Resources page.